Israel's Ecocide of Southern Lebanon

From the grapes of Rmeich and Marjeyoun to the olives of Deir Mimas and Kfarkila

Like Lebanon in international press, the country’s southern half seldom gets coverage locally unless it’s about friction with our unhinged neighbor.1

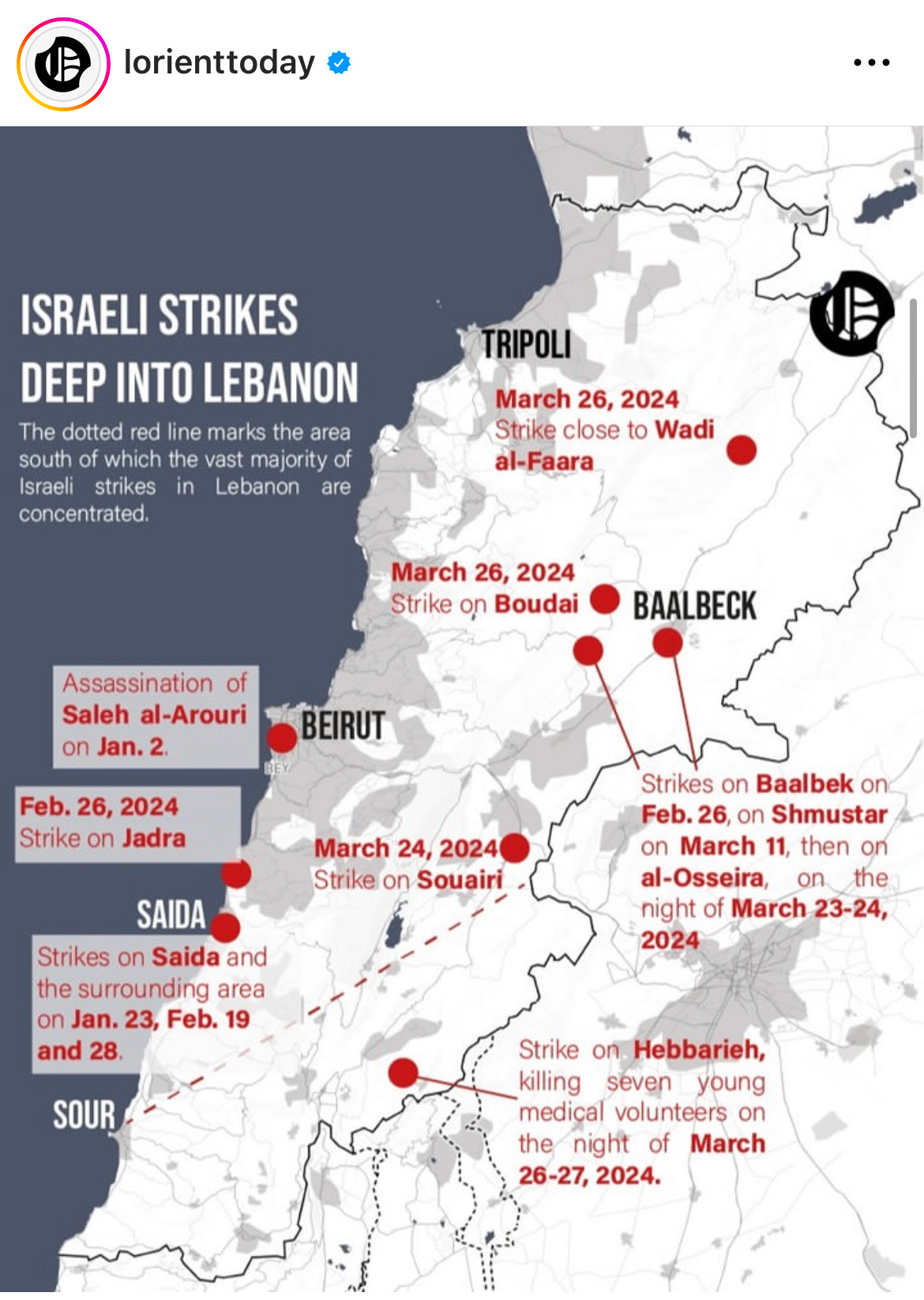

Since the exchange of fire on the border that began just a day after the October 7th Hamas operation, over 90,000 people have been displaced from southern Lebanon, according to the International Organization for Migration. However, Lebanese territory that’s considered “dangerous” isn’t as contained anymore as Israeli strikes have become more frequent and haphazard.

On March 19th, Megaphone News shared that Mohammed Chamseddine, a researcher at Information International, said the Lebanese economy “incurred losses of approximately USD 1.3 billion as a result of Israeli attacks since October 8, 2023.” He also estimates that 1,500 homes have been completely destroyed and 5,700 homes are damaged.

For more context and numbers on how the South is being impacted by the border escalation, read “Death, Displacement and Trauma: The Human Cost of War in Southern Lebanon” by Susann Kassem for The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP), published Jan 24, 2024 and “Universal Social Protection: A shield during armed conflict” by Jaafar Fakih from Civil Society Knowledge Center, Lebanon Support, published Apr 1, 2024.

Beirut Urban Lab has been logging the escalation over time, see their interactive dashboard. It’s updated weekly via its integration with Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED).

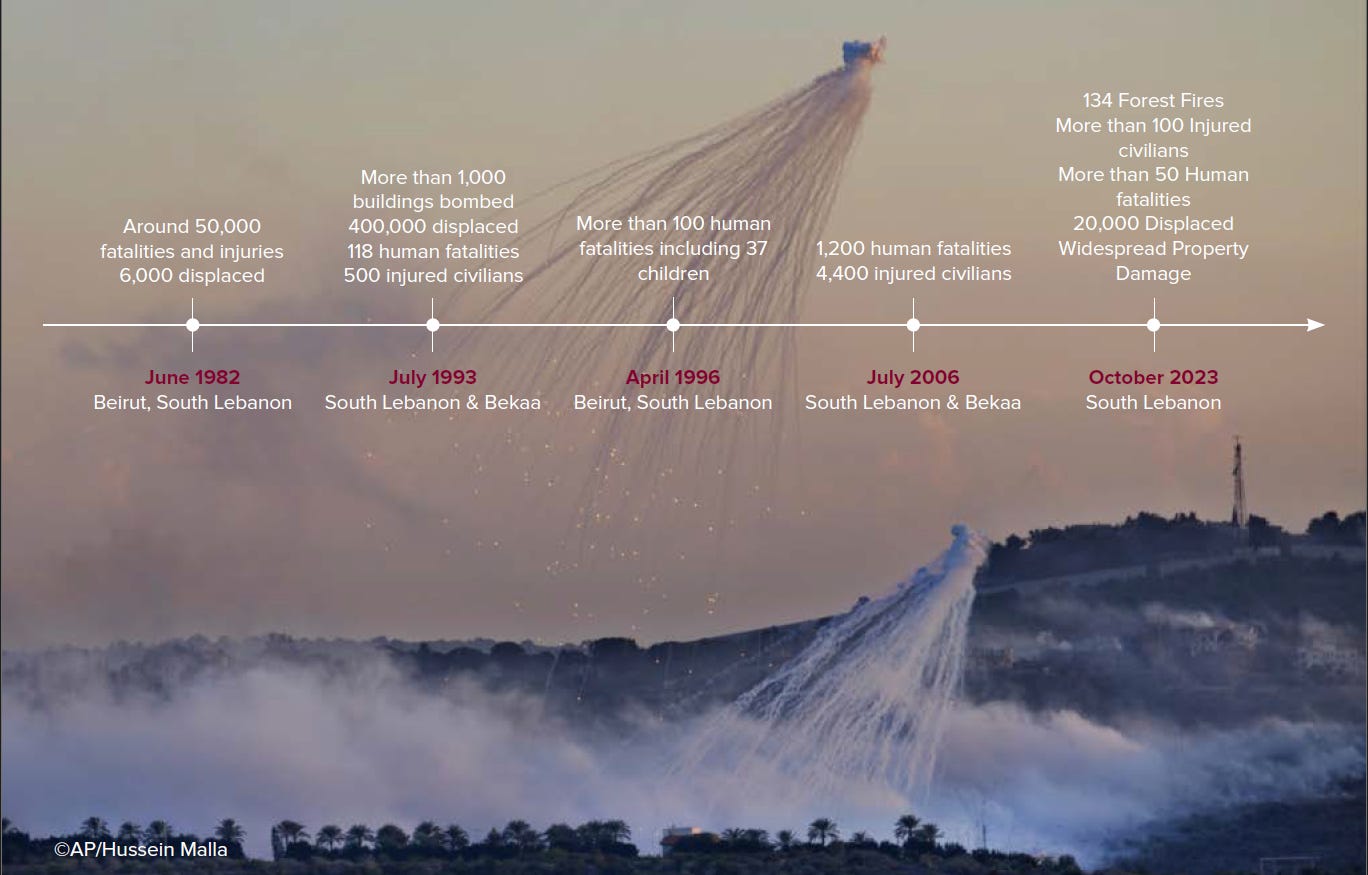

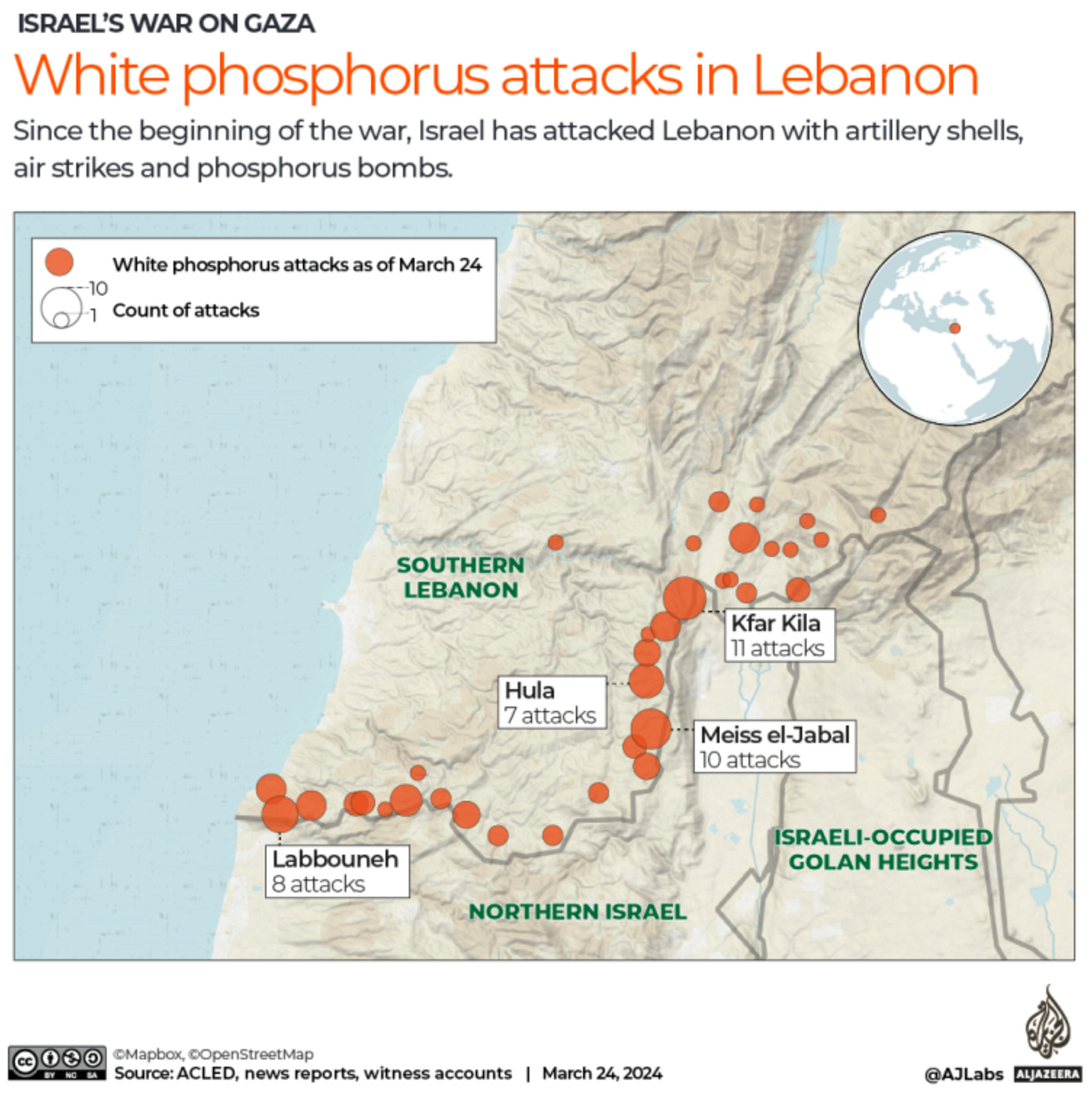

White phosphorous is the most obvious culprit in terms of contamination as its visible when dropped but there is fear of other contaminants being left behind as well. Looking at past events like the 2006 July War, the Israeli military could shower the area in MILLIONS2 of cluster munitions or [unknown toxic substances] just before a truce is put in place.

The American University of Beirut (AUB) hosted a panel by the Nature Conservation Center (NCC) and Issam Fares Institute (IFI). Titled "White Phosphorus Ammunition in South Lebanon: Impact, Management, and Policies", the panel also touched on the policy brief that’s been published by the NCC3 and shared some figures. According to the National Council of Scientific Research (CNSR), it is estimated that 800 hectares of land have been lost to fire, forests and fields alike.

BACKGROUND: WHITE PHOSPHORUS

White phosphorus (P4) is an allotrope4 of phosphorus. It is an incendiary weapon that’s typically used as a smokescreen in warfare. Its use is legal unless it is used indiscriminately over civilian-populated areas.

How (white) phosphorus was accidently discovered by a German who was searching for the Philosopher’s stone.

White phosphorus (WP) is reactive in air and ignites upon contact with oxygen5. It has a garlic-like odor and it continues to reignite until the phosphorus is depleted.

Very little is known about the impact of WP and its dispersed cloud as only the U.S. army and researchers in Gaza have studied it. It has been used in Gaza, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Ukraine. There are loopholes to justify its use in warfare such as “launching attacks from the ground”6 but Human Rights Watch has called for the closing of these loopholes as there are other alternatives that can serve the nonharmful purposes that Israel claims it’s using WP for.

According to Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine Dr. Thawrat El Zahran, WP’s effects upon contact with the body are two-fold: thermal burn and chemical burn. It can also inflict damage on the ocular, dermal, and respiratory organs7 and can have effects on the renal, cardiovascular and central nervous systems as well.

But it’s not just the immediate destruction and harm that are disastrous, it is the longterm impact on the environment and those that depend on it.

According to the NCC policy brief, “upon exposure to WP munitions, agricultural land is subject to decreased productivity. Existing plants could suffer from adverse effects including desiccation, dieback and wilting.” It also states that, “in Lebanon and the region, these incendiary weapons are damaging forest ecosystems and the endemic biodiversity they host.”

It goes on to explain that soil infiltration and the contamination of rivers and aquifers could affect the humans, flora, and fauna that live within this ecosystem. Phosphoric acid buildup can deplete the soil and increase erosion risk and waterbodies may be subject to eutrophication and algae overgrowth which is detrimental to all marine life.

The pattern of environmental destruction for the last four decades has led experts to believe that the goal of the Israeli military is to make southern Lebanon uninhabitable.

As their link to and dependence on the land is severed, southern residents will be forced to relocate further north leaving a deadzone that functions as a security belt for the existing northern Israeli settlements. Thus, Israel committing ecocide is not a side effect of the shelling, it’s the entire point. The desired effect is the southern residents evacuating the belt permanently because they’ve lost their homes, their livelihoods, or both. For some, it wouldn’t be the first time they’ve had to recover from such losses.

“Lebanon is divided into two parts right now, not 4 or 5. There is a part of this country that is a complete war zone,” said Rami Zurayk, professor of ecosystem management at AUB, during the NCC panel.

During the NCC panel, Dr. Zurayk said the soils in the area are calcareous (rich in calcium carbonate) which immobilizes phosphoric acid to a degree. The water table is also very deep so it may be untouched but fissures in the rocks could lead to groundwater contamination. Until the continuous attacks cease permanently and it is safe to assess the damage, no conclusions can be made about the extent (and then the impact) of the environmental crimes Israel is still committing on the South.

THE HARVESTS OF THE SOUTH

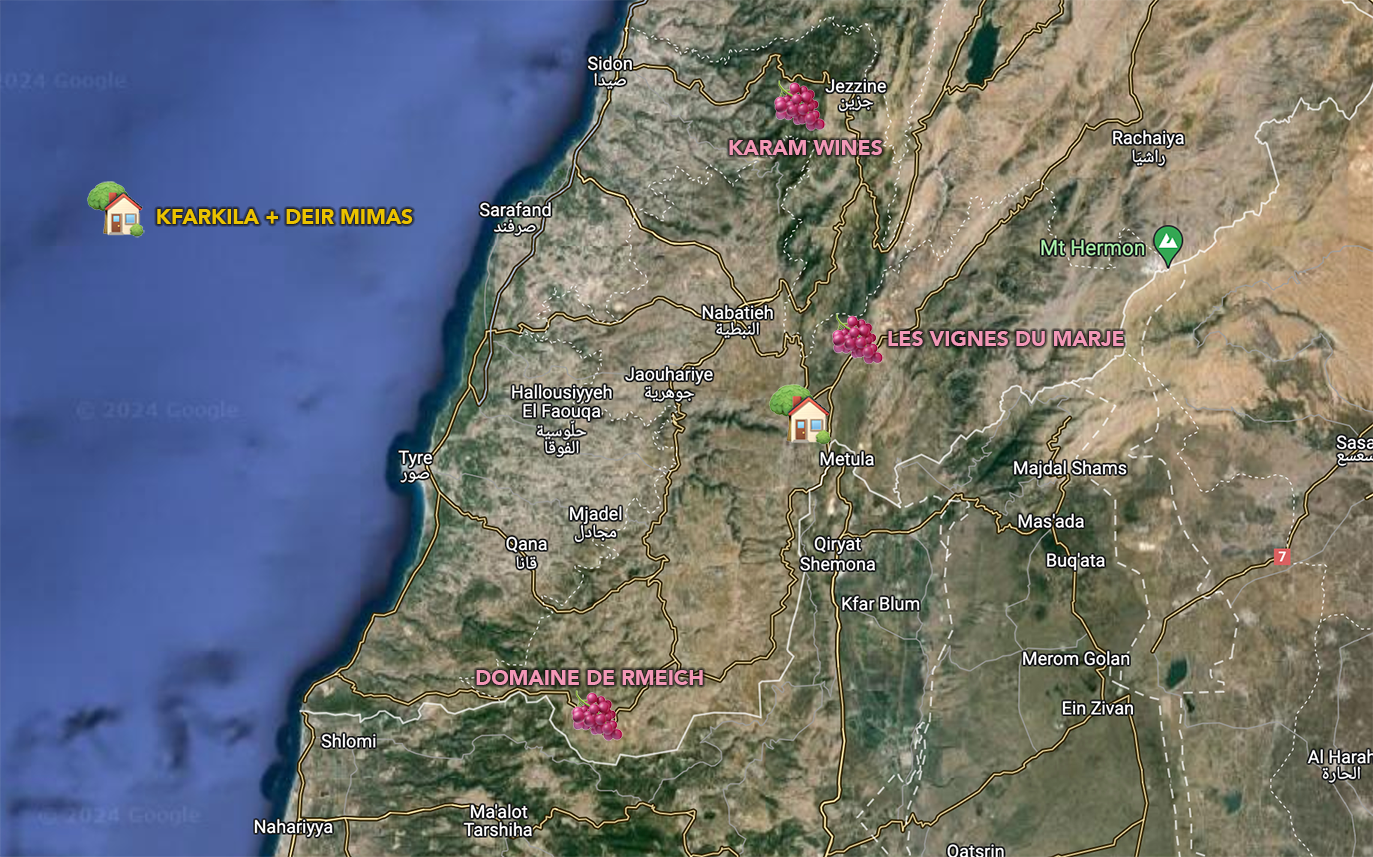

Karam Wines in Jezzine is the most established wine producer of southern Lebanon. In recent years though, new ones have popped up closer to the border, including Domaine de Rmeich of Rmeich and Les Vignes du Marje of Marjeyoun.

Domaine de Rmeich is a family-run winery that first started off as a passion project in 2017. The fruit is sourced from family-owned land within the border village, producing 30,000 bottles annually (majority is exported).

I spoke to Tatiana Makhoul who handles communications and domestic logistics from abroad. Their 2023 harvest was secured before the escalation began so they’re okay for the forthcoming year in terms of juice but it takes more than that to get wine made and sold.

Running things from abroad has meant that the Makhoul family is used to keeping the winery running remotely but, at the moment, there is no staff reporting for duty. Only a few family members (cousins) are on the ground in Rmeich: Dany, who checks on the facility and grapes, and Joseph, who makes sure raw materials are getting in. That’s the biggest issue right now for the family: getting trucks of labels, bottles, etc into southern Lebanon safely.

“As far as I know this isn’t a short-term conflict so we need to adapt to this new situation because we have no visibility as to when it will end. We have protocols in place to handle it for the foreseeable future,” said Makhoul.

Les Vignes du Marje, located around 10km from the furthest north part of Lebanon’s southern border, has a similar situation. Producing 20,000 bottles annually across 5 hectares, founder Carol Khoury said she’s been supervising the pruning of her vines via video with on-site workers to ensure the next harvest. Because the venture started under the guidance of Vigna Verde, their 2018 bottling that was released this year is the first vintage to be fully sourced from Marjeyoun vines8.

“May God spare us of this difficult war which we don’t know when it will finish,” said Khoury.

“People wonder how they can taste olives in my wine, it’s because they grow together. In the Bekaa, they don’t have zeitoun. That’s what’s special about our area,” said Khoury.

And it’s true. There are grapevines, tobacco, figs, and more that are dry-farmed in the South but the region is most known for its olives, supplying the country with more than a third of its olive oil. The olive harvest9 usually starts in early October but by the 7th, many families hadn’t even put down tarps under their sparse trees yet.

Darmmess is a brand of olive oil that’s sourced from groves in Deir Mimas, a village that’s a mere 2 km from the border. As a social enterprise, a big chunk of the profits goes to farmers and it is the only Lebanese olive oil brand that is certified high-phenolic10.

Rose Bechara Perini, founder of Darmmess, said their harvest - which began during the last week of September - had to come to a screeching halt because of the crossfire.

Deir Mimas groves haven’t been hit directly by WP; all shelling has been on the outskirts of the village. “Given all the efforts, time, and energy put into the brand, it’s really a pity to be in such a situation,” she said via Zoom. They had plans to be certified organic as of this year. “We’re living in a huge instability, we do not know what to do,” she said.

My dad’s family is from Kfarkila, the village next to Deir Mimas that’s been getting heavily hit by WP and more, and the village that has its own version of the border wall seen across Occupied Palestine.

Our main crop is olives. We distribute tanks and bottles of olive oil to our family and friends. We managed to press the last of our olives on October 7th and my dad & I returned to Beirut the next day. My extended family who live there evacuated not long after. Most of our newly pressed oil was left behind in my grandparents’ house in Kfarkila, in covered stainless-steel barrels.

Because the village is mostly deserted now, we zoom in on videos and photos of strikes that fellow villagers forward on WhatsApp. The phone-tree, IG aggregator accounts sharing footage of south Lebanon, and my typing “Kfarkila” in English and Arabic into X/Twitter’s search to see the latest tweets are how we guess the status of my family’s homes, graves, and groves. Beyond that, we know nothing.

SEEING THROUGH THE SMOKESCREEN

Growers and consumers are worried about what the shelling and airstrikes could do to southern crops for years to come and that worry is valid. However, assessing the damage can’t be done until we can get close enough to see it and conduct on-site data collection.

From those I spoke to, a major concern is that the press coverage of these pollutants will do more harm than good. Without trusted surveying and transparency of findings, cautious customers will understandably be hesitant to consume anything that comes from anywhere south of the Litani river. Assumptions could do more damage than the actual shells especially if their fears turn out to be unwarranted.

The public may have little trust in the quality control of local consumer goods but wine, olive oil, and other products that are exported will need to pass the rigorous regulations of receiving countries. There’s also mutual respect among producers as they know a tainted product can backfire on the whole category. “There's a lot of honor between us in the (wine) industry, we won’t let anything bad enter the market as it'll affect us all,” said Makhoul.

WHAT DO WE DO NOW?

As for those who don’t export, the produce of the solo farmer that operates on a small scale just to support and feed his own? Or the Syrian residents and refugees that are seasonal workers and can’t afford to be displaced (again)? They are both among the most vulnerable now as their safety and their livelihoods are at stake or have already evaporated.

“Israel’s deliberate and indiscriminate attacks, using white phosphorus against non-military targets, including agricultural lands endanger the livelihoods of thousands of farmers and agricultural workers, who are already excluded from the country’s labor code and are “…considered among the most vulnerable occupational groups in Lebanon.” The sector is also riddled with gender disparities. Women, who constitute 43 percent of the agricultural workforce, were found to earn half or two-thirds of the wages paid to men for the same amount of work. Thus, it is likely that the impact of the destruction of agricultural livelihoods will disproportionately affect women.”

- "Universal Social Protection: A shield during armed conflict" by Jaafar Fakih for Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support

It could take years before concrete conclusions regarding the environmental impact are reached so what do farmers and families do in the interim?

When I discussed this with Dr. Zurayk, he said, “you’re right to ask this question but the problem is you're asking it to the wrong people.”

“AUB cannot be responsible for all the farmers in the South. It’s a research institution, it can develop a methodology but at some point somebody needs to pick this up. Somebody who is vested with the authority, with the mission to make sure that your people are in a good place. Usually this would be the CNSR and the Minister of Agriculture. These are your two most important people who have been vested with this responsibility,” he explained.

While AUB is developing a methodology to log the damages across the South, implementing a national recovery (and reparations?) plan is the responsibility of the government and NGOs. However, the agriculture sector in Lebanon has long been neglected, the country’s coffers are empty, and there has been little initiative to or support on the ground beyond minimal streams of aid11. The NCC policy brief suggests next steps but the public have learned not to rely on the government in any crisis.12 This one is no different: there are no expectations for a regional rehabilitation plan.

When I asked if my family should be worried about our olives being contaminated, Dr. Zurayk said, “the fact that you’re concerned about it is reason enough to look into it.”

When we spoke of the hypothetical possibility of contaminants getting into plantlife, Dr. Zurayk focused on what we knew for sure as of right now: “Your main problem is the destruction of the livelihoods of people, the destruction of the ability of people to access their land, to use it - the physical impediment that is posed by this. These are our main problems for the time being. The long-term implications need to be looked at very carefully and this is what we are doing but this takes time because the more careful you are, the more time it’s going to take to be able to get your exact sampling from different locations, compare your samples, take them from different distances, have a look, make sure that your analytical methodology actually works. You need to address it as a scientist, rather than address it as just a member of the public relating an event. This is where we are, we’re at that particular stage.”

THE RESISTANT ECOLOGIES

For now, all southern residents, be they in the South or displaced elsewhere, are sitting ducks. This could also be said of all of Lebanon’s residents if we are to take the Israeli Defense Minister’s renewed threats to heart. As Makhoul said, “it’s something larger than Lebanon itself, it affects the region and I might even say on a global scale –it’s not something we can predict.”

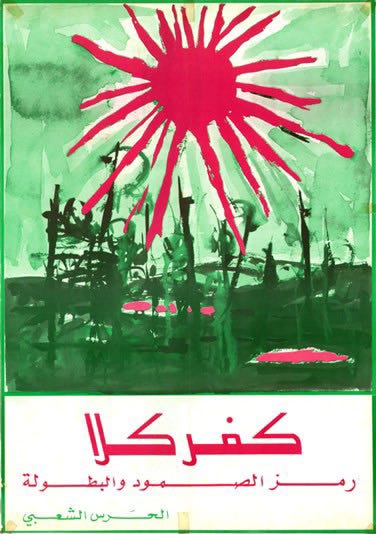

One common thing I’ve heard from all southerners I’ve spoken to (including those mentioned above) is that there are still people in these villages. Those that remain are incapable of leaving due to age, health, or finances. The stubborn few simply refuse to go anywhere else.

I’m currently reading Munira Khayyat’s book, A Landscape of War: Ecologies of Resistance and Survival in South Lebanon13, published in 2022. In it, she uses the agricultural borderland of the South to define “resistant ecologies,” or the networks that foster life in an otherwise uninhabitable place. She encourages us to think of war “in terms of continuity rather than rupture.”

As someone who has grown up without and within some state of war, I appreciate the idea of folding it into the narrative of our lives and wrapping it in resistance. There is war yet people persist.

We will return and the land will regenerate just as it has before. We remain rooted and linked. The South remains ours.

More Resources

“‘Ecocide in Gaza’: does scale of environmental destruction amount to a war crime?” by Kaamil Ahmed, Damien Gayle and Aseel Mousa for The Guardian

“Israel's toxic legacy: White phosphorus bombs on south Lebanon” by Justin Salhani for Aljazeera

“Israel’s Environmental and Economic Warfare on Lebanon” by Michelle Eid for The Markaz Review followed by their BURN IT ALL DOWN Roundtable Discussion

WATCH: Closing forum: Lebanon’s Priorities and Actions for a Green Transition, co-organized by AUB-NCC and the World Bank

”Olives, citrus, and bombs: Diana Salloum on South Lebanon’s agriculture” from Through the climate fog by Alex Simon

“In South Lebanon, Cultivating Resistance Against Israel’s ‘Substance from Hell’” by Dana Hourany and Yara El Murr for The Public Source

”Environmental Devastation by the Occupier: Unraveling the Silent Crisis” by Samer El Khoury for Al Rawiya

“An Olive Harvest Under Bombardment in Southern Lebanon” by Amélie David for Olive Oil Times

“South Lebanon on fire: The long-term implications of white phosphorus on the environment” by Sally Jaber for Raseef22

“‘Weaponizing the environment’: Israeli strikes burn South Lebanon’s farms, forests” by Philippe Pernot and Amélie David for L’Orient Today

“South Lebanon farmers fear losing this year’s olive harvest to bombs” by Sahar Al Bashir for L’Orient Today

”The ‘silent victim’: Ukraine counts war’s cost for nature” by Jonathan Watts for The Guardian

This was not how I wanted to introduce readers to the wineries of the South. Before October 7th, I had planned a short and sweet spotlight on the few wineries operating on lands beyond Saida. Alas, this is where we are now.

From The Public Source: “The Lebanese Army, UNIFIL, and multinational nonprofits such as Mines Advisory Group had removed 90 percent of these munitions as of last year; the remaining artillery was expected to be eliminated by 2026 — 20 years after the war.”

Although attacks are ongoing at the present, the policy brief will help communities be better prepared to a) deal with these attacks now and b) put a plan in place for what to do once the attacks stop.

Allotropes are various crystalline forms of an element that have different chemical and physical properties due to how the atoms bond together to create each allotrope. For example, common allotropes of carbon are diamond and graphite.

At a temperature above 34 degrees Celsius

From Salah Hijazi’s “Is Israel's use of white phosphorus in Lebanon and Gaza legal?” in L’Orient Today: "The use of incendiary weapons is governed by Protocol III to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, ratified by Palestine and Lebanon but not by Israel," said Lama Fakih, HRW's Middle East director. "Protocol III prohibits the use of air-dropped incendiary weapons in civilian areas," she added.

Inhalation of white phosphorus fumes can result in chemical pneumonitis.

In 2010, Khoury planted vines in Marjeyoun and worked with Vigna Verde, a family business of 5 brothers, to source grapes from Ainata to supplement the Marjeyoun production until her young vines there could meet the volume needed alone.

2023 was already an off-year and lower yields were expected due to heatwaves and fluctuating spring weather, the total volume of olive oil produced was further diminished because of the harvest being cut short.

“High-phenolic” olive oil contains at least 250 mg polyphenols per kilogram of oil. There are many health benefits associated it with high-phenolic olive oil yet globally, only 10% of EVOO products are considered high-phenolic. A study conducted on Greek olive oils proposed a new definition for high-phenolic olive oil: olive oils with phenolic content >500 mg/kg that will be able to retain the health claim limit (250 mg/kg) for at least 12 months after bottling.

Darmmess’ olive oil comes in at 500-630mg/kg across all batches.

Based on the NCC panel, the governmental response to the South has included leading seminars with healthcare/EMS, filing a complaint with the UN, and keeping in touch with local municipalities. “There is a disconnect between what the people need and what the state can provide,” said one of the panelists.

If you would like to donate to relief efforts in the South, you can donate to Beit el Baraka and select “South Lebanon Aid” in the support type dropdown.

This is part of how/why the Lebanese people rely on a combination of political parties (clientelism), social enterprises (the private sector), and NGOs to fill the gaps of the state. A destabilized Lebanon works to the advantage of the ruling class.

Amar Mustafa shared a thread of recommended books including Munira Khayyat’s. A free PDF of the introduction can be accessed here. You can also watch this webinar with Khayyat, hosted by Jadaliyya on Oct 13, 2023.

Thanks for taking the time to write this. ❤️

I just read this. and the fact that more than a year after publishing it, we are still in the same predicament ☹️